Once you understand the goals of your project the next important thing is to understand how those goals fit together.

If you are investigating several different topics that bear little relation to each other, then you will have a much harder time when it comes to writing up your project. You will have to obtain more data for your thesis, and writing the introductions, results, and discussions for each section will take more work.

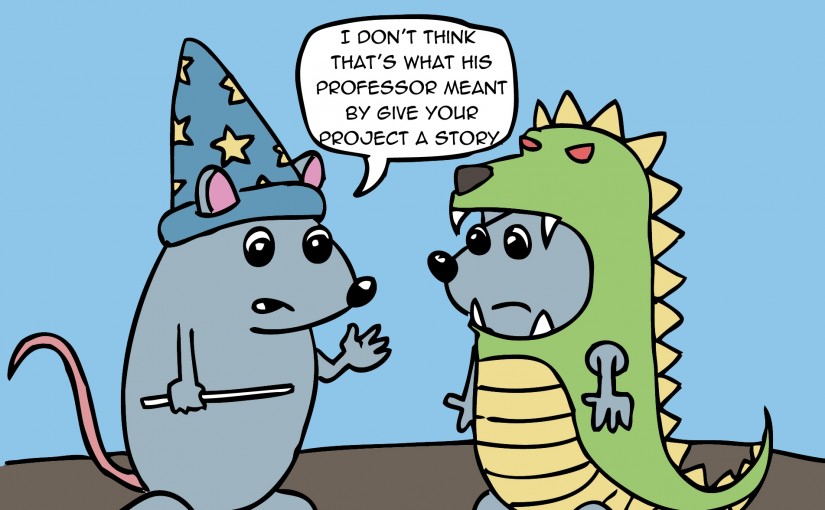

Before you start, you want to have some idea of a story that will join all the aspects of your project together.

Get Practical Tips- If your current goals don’t fit together in a cohesive story, think about any alterations you could make to both the goals and the story.

- A story can start by examining an effect. Then, if the effect is observed, it goes deeper into examining the underlying reasons.

- Don’t worry if you do not have a story immediately. Sometimes the effect must be observed before the reasons can be explained. In such cases, a backup plan is extra advisable (see Always have a Backup Plan).

- A story does NOT mean plan out what results you are going to get. Your story should account for every possible outcome of the experiments you are doing, otherwise you run the risk of biasing your data.

- DO NOT wait until the end to fit your disjointed project together into a single story. This will lead to panic and a series of rushed procedures that will be very bad science and probably won’t work.

Read Personal Perspective

My PhD was very well structured, which helped me immeasurably in its timely completion. Most of the people I know who struggled to finish by the deadline had detached or incoherent stories.

Some students didn’t know where there work was leading, which made it difficult for them to design experiments, and led to a slow start and a rushed end. Others knew exactly what their project involved, but couldn’t fit all the different aspects of it together. It made their data much more difficult to publish because journals rely more than anything on a coherent story. Not even the lower impact ones will accept random blocks of data that offers no combined conclusion.

When people have done joining experiments to link their data it is always easy to spot in journals because these are the sections which look rushed. They don’t always have good controls, the images and supplementary data are usually poor or absent and they are generally referred to in the text as little as possible. This is bad science, and it is worth avoiding if you can.

Have you made similar mistakes? Share your experiences or feelings about this guideline in the comments below, or just give it a thumbs up.