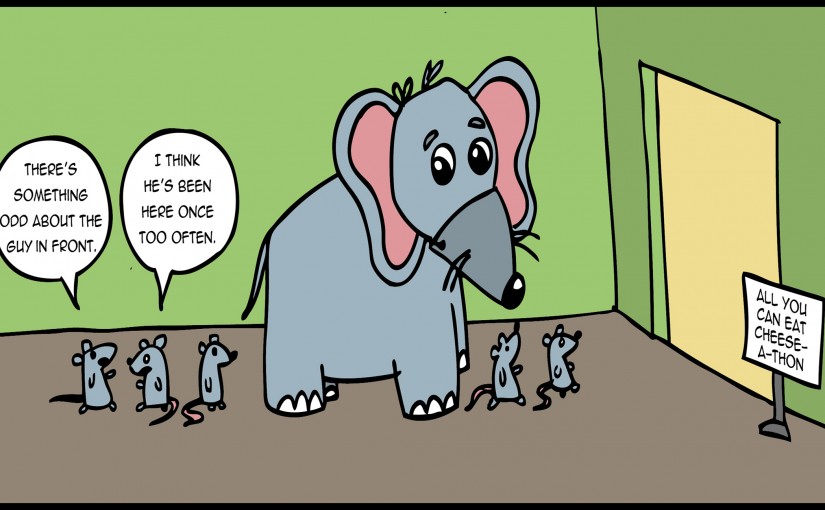

One major malfunction in thesis construction is to write about what you want to discuss rather than what you need to discuss. Naturally, we are inclined to spend time on the things that interest us and avoid the topics that send us progressively further into comas as we type each word.

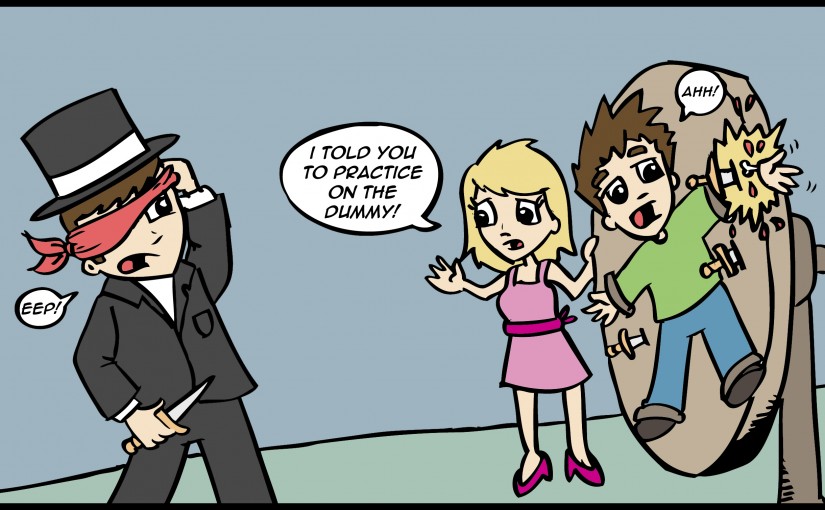

At the point of starting, many people think their thesis will be perfect, or at least the best thing they’ve ever written. The result is that they start by reading fifty papers for the first sub heading and writing almost as many pages. This is not a good strategy. Even if this first subheading is not far too detailed, continuing at the same level will be exhausting and you run the risk of burning out.

This is not say your thesis shouldn’t involve a lot of effort, but try and keep your expectations realistic.

Get Practical Tips- It is a good idea to rate the importance of each section so that you know roughly how much time you need to spend on it.

- No one will congratulate you on the size of your thesis. Your examiners are busy people and the more you write the more they have to read. Cut bits if they aren’t relevant. It may hurt, but it needs doing.

- If you are struggling to write a section, make bullet points of all the important bits you have covered thus far and the ones you still need to do. Come back to it later with fresh eyes.

- When writing the sections you find most interesting, repeatedly refer back to your story and ask yourself if what you are writing is relevant.

- Don’t ignore the bits you find boring. If your examiners see noticeable gaps in certain areas, then they will spend more time on these in the viva and you may have to add them in your corrections.

Read Personal Perspective

When I started writing my thesis, I was going to read every paper ever written that was remotely related to my project. It was going to be perfect.

This is impossible.

After a few very thoroughly researched sections, I semi-quickly realised that the workload was unsustainable. Unfortunately, I’d started on the more general topics which were not so relevant to my project. It made for a good opening to my thesis, but that work would have been better placed in later sections where more detail was expected.