Category: Referencing & Document Control

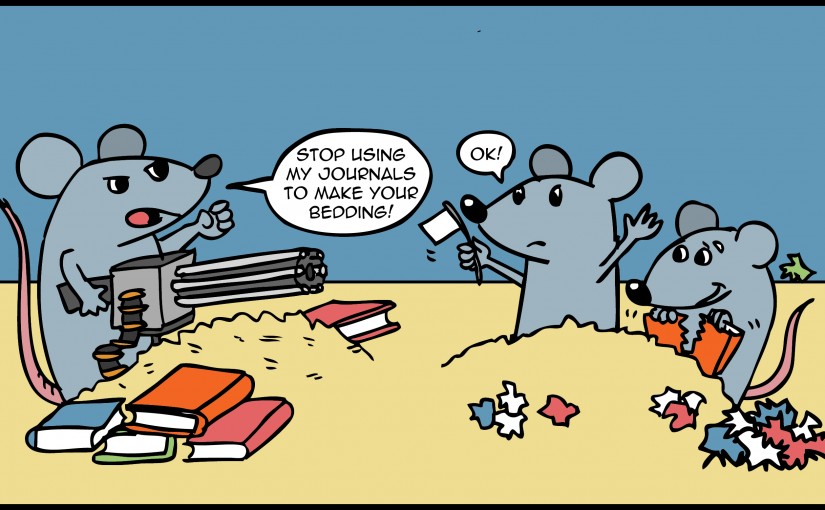

Organise Your Lab/Note Book

Make sure you have the main protocol written up and visible whilst you carry out the procedure. You will probably also have a notebook for rough notes.

The mistake is to assume you will never need to look at these again. Most likely you will, at least for some of them. So don’t jot numbers and names down with no reference to what they mean. Put a date and title at the top and use comprehensible language to show what each bit describes. It doesn’t have to be full sentences as long as you still understand it in five days’ time.

Not only will this help you remember which sample/individual corresponds to which data set, but it will also help you analyse mistakes, or find where changes might have improved the procedure.

Get Practical Tips- Don’t ever use loose bits of paper. They get lost.

- Date everything, including your electronic files and rough calculations.

- Write down any changes you make to procedures, so that if the outcome changes you have some possible explanations.

Read Personal Perspective

I did some experiments where I had to add about 10 different inhibitors to cells and work out the best concentrations for each. Each time I scrawled down the values for each inhibitor without labels. I knew at the time which was which, but a few weeks after when I came to analyse it, this information had long since departed me. It was stressful and time consuming to work out which concentrations I had used for which drug at which time.

Organise Your Results

Analysing results can be boring. The experiment is basically complete and you want it out of the way as soon as possible. However, it is likely that even if the results are bad you will be back one day staring at the spreadsheet trying to interpret what it all meant.

When you write papers or your thesis you won’t remember which of your myriad spreadsheets are the ones you want. Therefore, it is best to keep a consistent layout across projects and title every column and row so they are instantly recognisable when you return to them.

Get Practical Tips- In Excel, keep a copy of all your graphs on a separate sheet (not a separate document), which should be labelled graphs. Then you can instantly see if a spreadsheet contains good data or not.

- Label all your graphs with the maximum amount of information. Don’t leave the axis as x or y or % Change. They are meaningless. Write exactly what you measured in the axes.

- Try as much as possible to utilise (and title) different sheets (again NOT different documents) for different tables of data. If you have to scroll through thousands of lines of data with other tables beneath and to the side, it quickly becomes uninterpretable.

Read Personal Perspective

My bane was always the unlabelled graph. I would even show them to my supervisor and he’d just look at me blankly and say, “What does it mean?” At the time it was obvious to me as I’d just done it, but he – and myself in the future – had no idea. It’s so quick to label an axis, and it takes so long to interpret one that isn’t labelled. When I wrote my thesis I discovered this, but it was too late by then.

Link Your Work

Before computers, linking work was easy as everything had to be written up in the same lab book. Now we have Microsoft Word and Excel documents; other stats packages; internet sources; data on many different machines; and manufacturers protocols, all on top of our hand written lab books and notebooks.

This mishmash of paper and virtual documents makes for an organisational nightmare, and requires some thought to be organised so that it is of any use.

As much as possible keep all data about one project together. When this is not possible, one mechanism is to use an acronym of the project title which identifies all your work to the project it belongs to.

Get Practical Tips- On your computer, divide your research up into folders for each project, labelling each folder with the project acronym. Store all your data and protocols relevant to that project in that folder.

- For each replicate add a number to the acronym, and make folders for each replicate within the project folder. Make sure you write the outcome and the reason for doing the replicate on the results. You could even add a one letter identifier to the file name so you can quickly see whether it contains good data, “G” or bad data, “B”.

- Date everything, as this provides a failsafe for linking bits of work on different computers, or from computers to lab and notebooks.

- Copy all data off communal machines as soon as possible.

Read Personal Perspective

When it came to writing my thesis, I spent ages trawling through data with incomprehensible file names. Many of my graphs were already in journal papers, but some of them needed subtle changes and others had disappeared from the stats software, so they needed to be done again. Some of these sets of data were almost three years old, and I’d long forgotten what it all meant. If I’d put it all in separate folders with succinct file names it would have taken a fraction of the time to remake those graphs.

Label Everything

Every lab throughout every country in the world contains thousands of tubes storing mystery liquids and solids, which are useless and potentially dangerous.

Computers are cluttered with folders and files that might as well read, “never_open_this_again.file” because the unlabelled content is meaningless to anyone but its long departed creator.

Label everything as precisely as you can. Make sure it contains the project name/acronym, the date, replicate number, and any other info required to identify it.

Get Practical Tips- Think about your labels for more than the minimum number of seconds. If you have just written a few words, then you will probably have missed something.

- Date everything. If all else fails, the date may still save you.

- When you date your files on computer, write them backwards, starting with the year then the month and then the day, so the computer will automatically put your files in chronological order.

- Computers have lots of memory, so write accordingly long file names. You can never have too much information immediately visible.

- Even if you are only using something for a few minutes, it is still worth labelling. You could drop things or mix them up, and the briefest loss of concentration could otherwise leave you unable to continue.

- Keep all the datasheets of the products you order in a draw, separate from everything else.

- For papers, copy and paste the whole title into the Save As.

Get Wet Lab Tips

- If the tube is too small to label properly, put it in a bag and label that.

- If the material is difficult to write on, write on a piece of paper and then stick that on.

- Be careful you don’t label liquid containing tubes with pens that will dissolve in the solvent.

Read Personal Perspective

I once did a proteomics study where I labelled each tube in a red pen only to find that the alcohol in the tubes had spilled through the holes in the tops and leached the pen back in with it. The result was a series of tubes with varying degrees of pink in them, and the uncertainty as to whether the degree of pinkness had affected the results.

Store Your Journal Papers Wisely

Everyone likes to read things on paper rather than on the computer, but the truth is that there are huge downsides to storing papers this way:

- They are easily lost

- They are difficult to organise

- They form needless clutter

It makes much more sense to store all your papers on the computer, and there are several programs available for doing so. You can highlight and make notes about papers just as you can do by hand, with the benefit that there are search boxes to locate papers and information within papers.

Get Practical Tips- Every paper you want to read or reference later should be saved as a PDF on your computer before you add it to a library such as Readcube, Mendeley or Endnote. If your other libraries get deleted or overwritten – which can happen – then you at least have all the PDFs.

- Save the PDFs with the full title of the article, not just an abbreviation or vague description, and organise your folders by topic so you can see what papers you have read in each area of your research.

- You can always print them out to read, but if you intend to refer to them later a virtual copy is advisory. One exception is when there are bits of protocols that you might want to cut out and stick in your lab book.

Read Personal Perspective

I printed out most of the papers I wanted to read, and most never got read, which was pretty wasteful. Beyond that, the stacks of papers for my thesis were stored in piles in my room, numbered so that I could just write (ref 10) and not interrupt the flow of writing. When it came to putting in all the references, I thought I could just sit down in front of Breaking Bad and plug them in.

WRONG.

I still don’t know how, but several of them had gone missing, and other times I had written down the wrong reference number in my thesis. Referencing took a whole lot longer than it would have if I had both used electronic documents and referenced as I wrote.