Strategies for Formative Assessment

Evidence about student understanding can be exploited and used formatively by the teacher, learners or their peers at different steps of the learning process and with different purposes. In particular, Wiliam and Thompson (2007, adapted from Ramaprasard, 1983) focus on three central processes in teaching and learning:

- Establishing where the learners are in their learning,

- Establishing where the learners are going and

- Establishing how to get there.

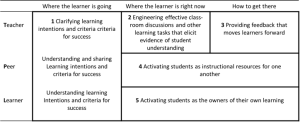

They state that formative assessment can be conceptualized in five key strategies (see figure below) that enable teachers, peers and students to close the gap between the learner’s current understanding and the learning intentions:

- Clarifying/ Understanding/ Sharing learning intentions and criteria for success,

- Engineering effective classroom discussions and other learning tasks that elicit evidence of student understanding,

- Providing feedback that moves learners forward,

- Activating students as instructional resources for one another,

- Activating students as owners of their own learning.

Figure 1: Key strategies of formative assessment (Wiliam & Thompson, 2007)

Figure 1: Key strategies of formative assessment (Wiliam & Thompson, 2007)

In the FaSMEd project, these expressions by Wiliam and Thompson (2007) are understood in a broader sense involving all agents of the learning process in a classroom: while, in activating strategy 2, it is the teacher’s responsibility to provide suitable tasks, questions or prompts that elicit evidence of student understanding, students or their peers can gather information on where the learner is at a certain point in his/her learning by working on these tasks or participating in a classroom discussion as well as by evaluating their/their peers’ work. The other strategies can be activated at the teacher’s as well as the peer’s and the student’s levels. For example, not only the teacher but also the learner or a peer can “provide feedback that moves learners forward” (strategy 3). Moreover, strategy 4 could be activated both by the teacher and by peers (who could activate themselves as instructional resources for one another), since the communication and comparison among students about their current conceptions can represent an important feedback for them. Finally, strategy 5 can be activated both at the teacher’s and at the learner’s level, because the learners could activate themselves as owners of their own learning when they reflect on their own learning process by using metacognitive strategies.

References

-

Ramaprasad, A. (1983). On the definition of feedback. Behavioral Science, 28(1), 4-13.

- Wiliam, D., & Thompson, M. (2007). Integrating assessment with learning: What will it take to make it work?. In C. A. Dwyer (Ed.), The Future of Assessment: Shaping Teaching and Learning (pp. 53-82). Yahweh,NJ:Erlbaum.