Dr Chloe Duckworth and Dr Stephanie Piper

School of History, Classics and Archaeology

Humanities and Social Sciences

What did you do?

We developed a style of teaching that engages undergraduate and master’s students through practical group activities and the use of bespoke online resources, creating a relaxed learning environment and cementing knowledge by tapping into different ways of learning.

Graduate Framework

This approach develops the following attributes:

- Critical Thinkers

- Creative, Innovative and Enterprising

- Curious

- Collaborative

- Engaged

Staff can find out more about the Graduate Framework on the University intranet.

How did you do it?

This style of teaching is used in the module ‘You Are What You Make’ (of which there are two versions, for undergraduate and master’s students). The module is aimed at teaching students about the social context of ancient technology. It is rooted in anthropological theory, and employs evidence drawn from anthropology, ethnography, experimental archaeology and archaeological science. It covers a broad swathe of the past, from early stone tool use to the invention of glass.

As well as lectures, seminars, and set readings, we utilise:

• Online educational videos

• Two-hour practical classes focused upon making

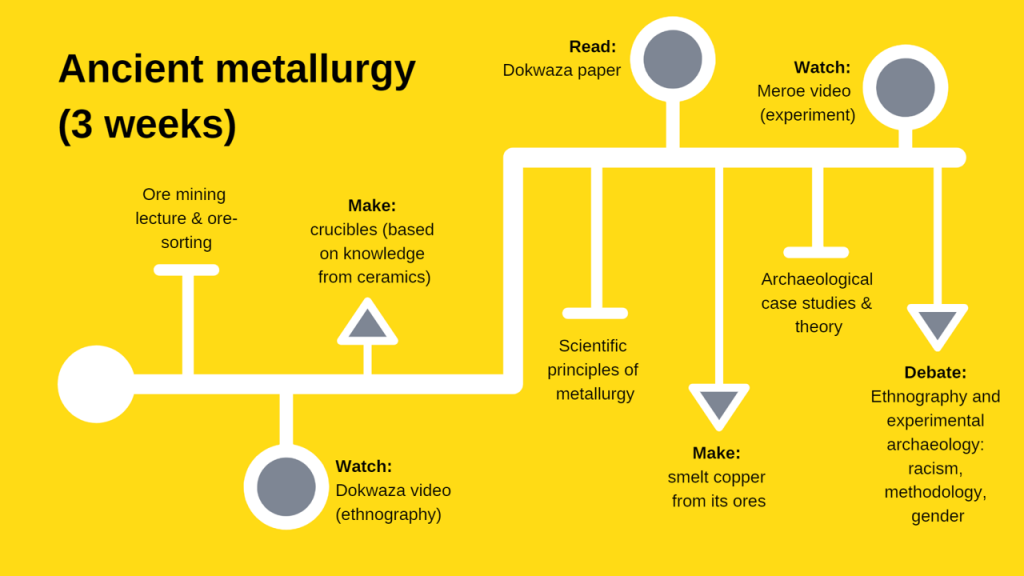

To illustrate the structure of the module, we will share with you a three-week section that covers ancient metallurgy. Each week starts with a one hour lecture, introducing scientific and theoretical concepts. Students are also expected to watch two online videos, each about an hour in length, and to read a paper, and these form the basis of a discussion and debate in the final week.

Two practical classes, each two hours in length, are held in weeks one and two. In the first, students are asked to apply the understanding of ceramics they gained in previous weeks to make a suitable crucible. In the second, they follow instructions to smelt copper from its ores. Both activities require them to work together and self-organise as a group.

During practical classes students are relaxed, and have the opportunity to chat with one another. In conversation, students often return to the theoretical concepts they have been learning, or reflect upon the way that ancient technologies are understood from an academic perspective.

The act of physically recreating the technologies taps into a different type of memory, and students easily retain the full operating sequence, bypassing the need for extended repetition of basic concepts and allowing us to focus directly upon more complex, challenging, social questions. The practical and experimental aspects of producing objects provides them with a deeper understanding of the skills of people in the past to produce artefacts recovered from the archaeological record. Interpreting the stages in the manufacture of objects is a key skill in archaeology, and by recreating this it bridges the theoretical and analytical concepts of artefact analysis introduced in other modules.

As well as video resources made by others, one of us (Duckworth) creates bespoke videos for the YouTube channel ‘ArchaeoDuck’, and these are sometimes used in teaching. For example, a pair of five-minute videos explaining the basic principles of radiocarbon dating is used in a class for master’s students, along with an online exercise and archaeological case study. This ‘outsources’ basic learning to the students’ own time in manageable, brief modules that can be watched as many or as few times as necessary for the individual learner, allowing us to focus in class on more complex discussion and debate.

The idea of using physically engaging, practical activities may seem off-putting, especially to those from very text-based disciplines. What we would like to emphasise is that we were not trying to teach practical skills per se, but using these classes as a way to engage the students, and to help cement and augment their understanding of concepts and theories that are more usually obtained from reading alone (and often poorly retained as a consequence).

The two-hour practical classes were oases of relaxed learning, in which students had the time to mull over, discuss, and apply theoretical concepts drawn from their reading. It requires some self-discipline from the module leader to reduce the amount of academic reading set in preparation for classes, but by introducing the online video as an alternative form of preparation, we found that classroom engagement increased significantly, and students were equally – if not more – likely to engage with the set readings and delve into the longer reading lists.

Student Voice

“I think learning through touch, and interaction with tangible things, is extremely effective and engaging, making the topics we looked at even more interesting, and the classes really fun and enjoyable … This type of teaching – hands-on, practical, looking at process and manufacture – opens a door to engaging people without academic training, or people from other disciplines, which I believe should be at the heart of what we do and our motivation for studying anything!”

Holly Holmes, MA Archaeology student

“This module was fun and challenging, transcending period-specific interests and addressing fundamental questions about the production of the material culture which archaeology relies on for pretty well everything else it seeks to do as a discipline…”

John Pearson, MA Archaeology student

Why did you do it?

The importance of material culture, and the physical act of making, has been greatly undermined in recent years. We want our students to understand the power of materiality in tapping into the social life of past people, but also to develop a better understanding of past technologies by experiencing them.

Does it work?

The relaxed approach offered by the practical sessions, and the use of videos in student preparation for classes, seems to be particularly welcomed by a student body which is under great pressure to read large volumes of academic writing and produce coursework of a consistently high quality. Yet students clearly learn just as much through these multimedia approaches, and may retain the information for longer.

Students felt a great deal of pride in the objects they produced. Even where certain techniques did not work, these ‘failures’ were used by them as learning experiences by which to improve and ‘succeed’. This self-assessed and peer-assessed informal feedback (i.e. trial and error, discussion) allowed the students to reflect on their learning to develop their skills, whilst taking the onus off the instructor to provide more structured formative assessment.

Contact Details

Dr Chloe Duckworth, Lecturer, School of History, Classics and Archaeology

Dr Stephanie Piper, Lecturer, School of History, Classics and Archaeology