Dr John Hedley, Senior Lecturer

School of Engineering

Faculty of Science, Agriculture and Engineering

What did you do?

Introduction to Instrumentation and Drive Systems (MEC3027) is a module where students undertake an assignment worth 60% and a computer-based exam worth 40%. The assignment is based on developing skills whereas the exam is based on a student’s background knowledge of the subject.

All possible questions for the NUMBAS PC exam are released to the students during the teaching aspect of the module, a selection of which are then picked for the exam. The key point of this approach is that the students get to see, practise, and ask for advice on all the exam questions prior to taking the exam.

Who is involved?

Dr John Hedley, Senior Lecturer, Engineering.

How did you do it?

The exam uses the NUMBAS assessment software. There are 4 aspects to the approach:

Firstly, the question set is large enough to cover every learning aspect of the module. The exam is chosen using a subset of all the available questions. The downside to this is that it takes a lot of time to set up the complete range of questions. The upside is that once it is done, any future exam is easy to arrange, mark and provide feedback by simply selecting a different subset of questions. This is particularly pertinent now due to the increasing student numbers and the need for first, second and extraordinary exams being required.

Second, the exam is computer marked and marks are awarded for answers only, not method. To account for occasional mistakes in a calculation, there are a lot of small questions to answer. Therefore a small mistake makes little difference to the overall mark. Students are made fully aware of this aspect of the marking at the start of the module.

Thirdly, the questions are arranged so that a student cannot memorise an answer but must know the required learning outcome. This is achieved by ensuring every question has multiple variations associated with it. Three examples of how this is achieved are:

- A basic numeric question can easily be set so that different numbers are used each time the question is run, therefore the student needs to know technique of solving and not the numeric answer.

- In a multiple choice / multiple answer type of question, multiple variations of the question are achieved by, for example, programming 5 correct answer and 10 false answers. The question then selects 2 random correct answers and 4 random wrong answers each time the question is asked. Therefore the student needs to learn all the possible correct answers, i.e. achieve that particular learning outcome.

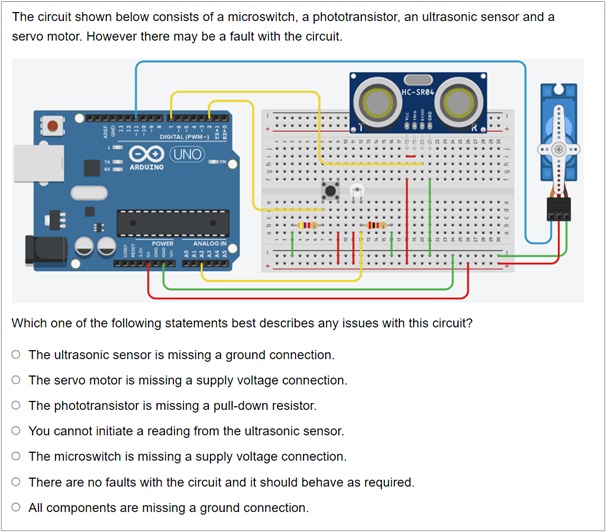

- A traditional paper-based exam question would ask the student to draw a circuit to drive a motor and take a sensor reading. In the NUMBAS version of the question, the circuit is drawn with a fault in it and the student needs to identify the fault from a list of possible options. The question is setup so that a different fault appears each time the question is run therefore the student needs to learn what the correct circuit is and then identify where a fault might be occurring. The image in figure 1 shows an example of this, for this particular run of the question, the ultrasonic sensor trigger pin is connected to a permanent high setting so you cannot initiate a reading from this sensor. The next time the question is tried, a different fault will occur.

Figure 1: Example of a NUMBAS question

Finally, the exam is open book so students can make notes of any or all questions prior to the exam and use these during the exam. The exam timing and number of questions used is arranged so that a student cannot complete the exam unless prior preparation is done. For example, a question may involve using 3 different equations to obtain the answer which will take the student 5 minutes to complete. But the question only allows for 2 minutes if the student wishes to complete the whole exam. However, if the student practises this question and makes notes, they will see rather than entering numbers into each equation, the equations can be combined to form a single equation that can be used to answer the question within 1 minute. If the student asks for help on such a question, I will discuss the 3 required equations but then it is up to the student to demonstrate their analysis and creative ability by re-arranging for themselves to a form suitable for the exam. Therefore the exam not only assesses understanding, it is also assessing how much preparation the student has done during this module. The students are made aware of this aspect during the module introduction.

Why did you do it?

Exams will always be stressful for students and can be regarded as a bit of a lottery on whether something a student has revised is what actually appears in the exam. In addition, paper-based exams in previous years demonstrated a lack of understanding of what was expected in the answer, particularly when a student’s English language was weak. This approach addresses, to various extents, each of these aspects and students know exactly what to expect and exactly how it will be assessed.

Does it work?

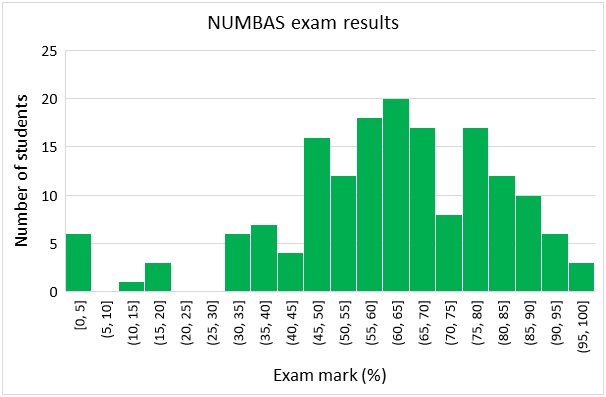

In terms of differentiating and assessing student abilities, it works exceptionally well, the histogram in figure 2 shows a breakdown of the spread of marks (2023-2024 cohort). The mean can simply be tweaked by adjusting the time per question ratio (which comes with a little experience but can in the first instance be scaled on the harder side and moderated upwards until an appropriate balance is found). The spread is adjusted by the range of question difficulty on offer, fortunately this is not something I have needed to adjust as it has worked well from the outset but does give the examiner an option if they wish to try and adjust the distribution of marks.

Figure 2: Breakdown of the NUMBAS exam marks

From a student perspective, Canvas records reasonable accessing of the exam questions from the students with 156 (out of a 166 cohort) reviewing the first set of questions an average of 3.7 times, this falling to 119 students viewing the remaining six sets of questions an average of 2.8 times (the drop in student numbers may possibly be attributed to students deciding to work in groups). When this approach was first trialled, there were several initial complaints about why an answer had to be ‘exactly correct’ with no method marks given so now the rational for this is clearly explained and this year there were no issues from the students.

The approach also allows for instant feedback where a student can see the exam results as soon as the examiner allows it and then review where they went wrong (this can potentially be the same day). Unfortunately, the current University rules (2024) do not allow this and marks have to be reviewed by the Board of Examiners before release which typically happens well after the exam, at which point the students have moved their focus onto the next module or have left for the year. This aspect of mark release from a computer based exam is something I would like to see reviewed so students have the opportunity for same day feedback.

One final benefit is exam checking. This is traditionally done by an academic colleague but as students get to see the exam questions prior to the exam, there is effectively a large cohort of people checking question suitability and accuracy. As the same questions are then used in future years (with possibly minor tweaks or additional questions added), the pool of questions become well reviewed. It also gives students the opportunity to feedback on how they are being assessed prior to the exam taking place.

The Graduate Framework

This case study demonstrates the following attributes:

- Future focused

- Creative, innovative and enterprising

- Digitally capable

- Engaged